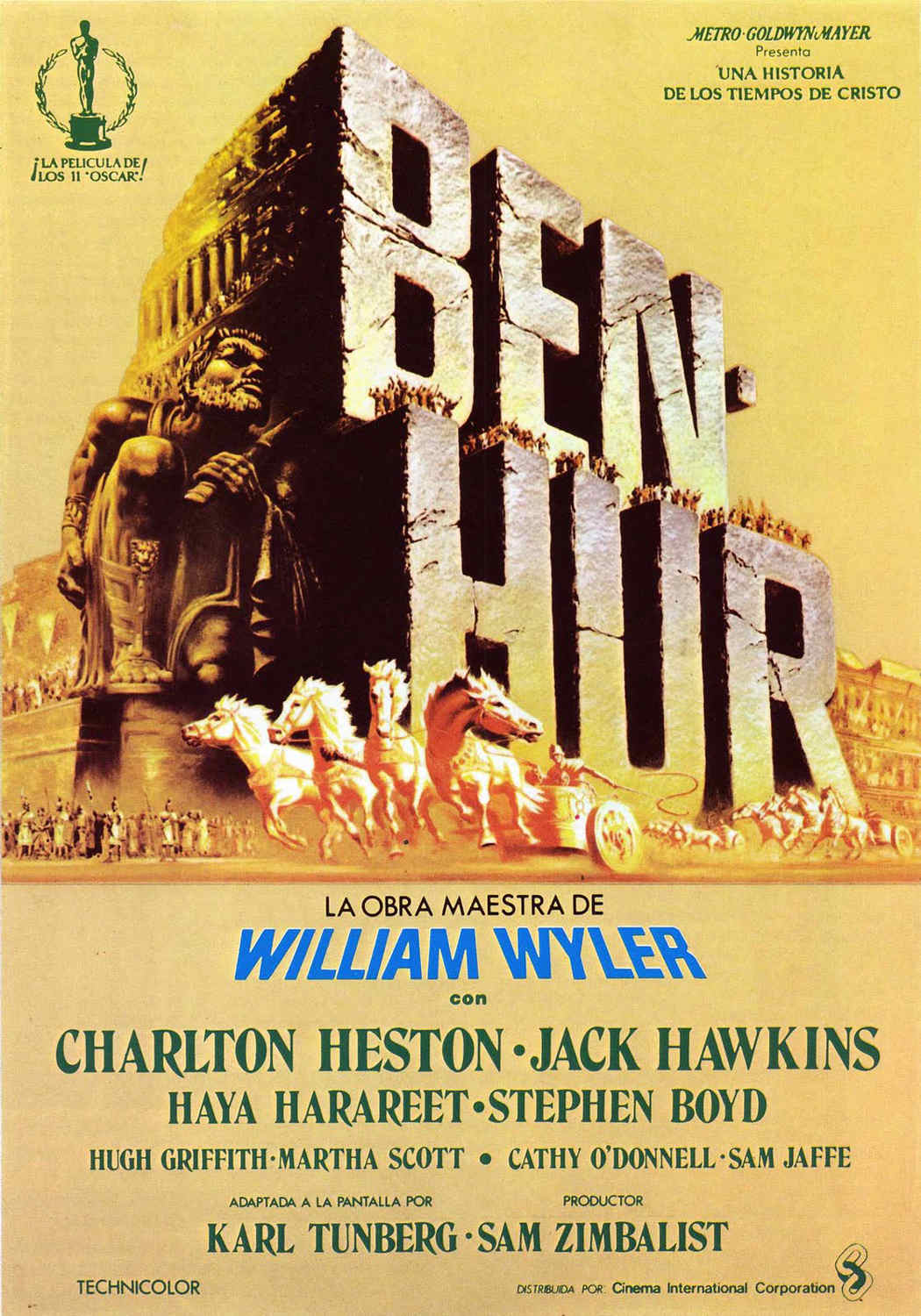

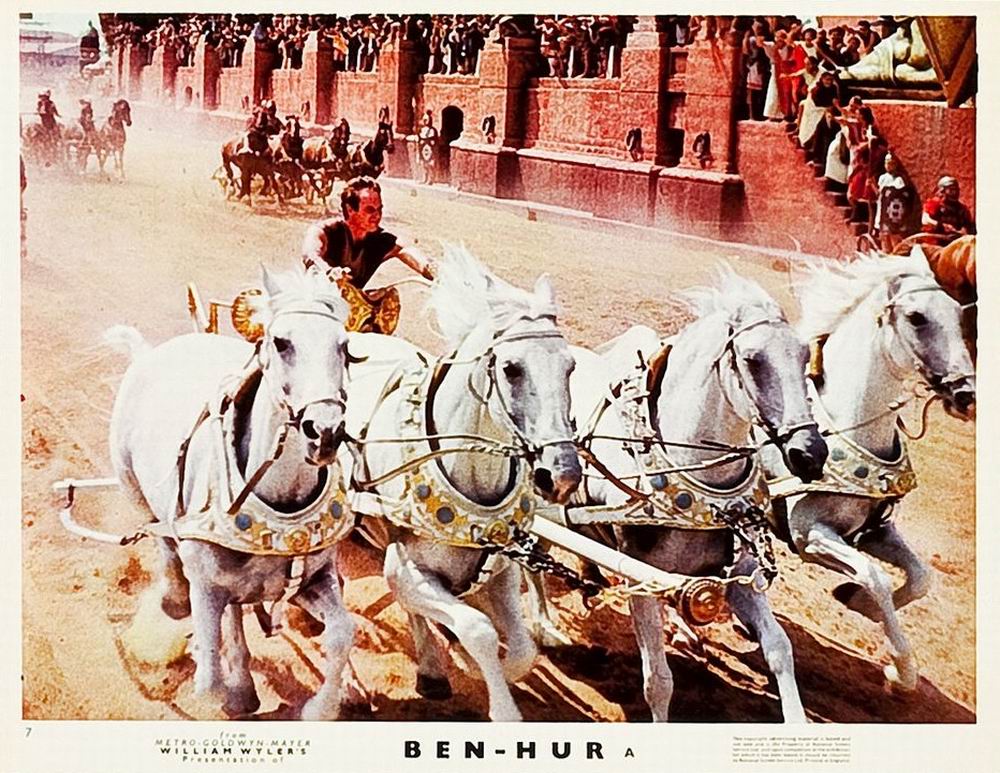

The 1959

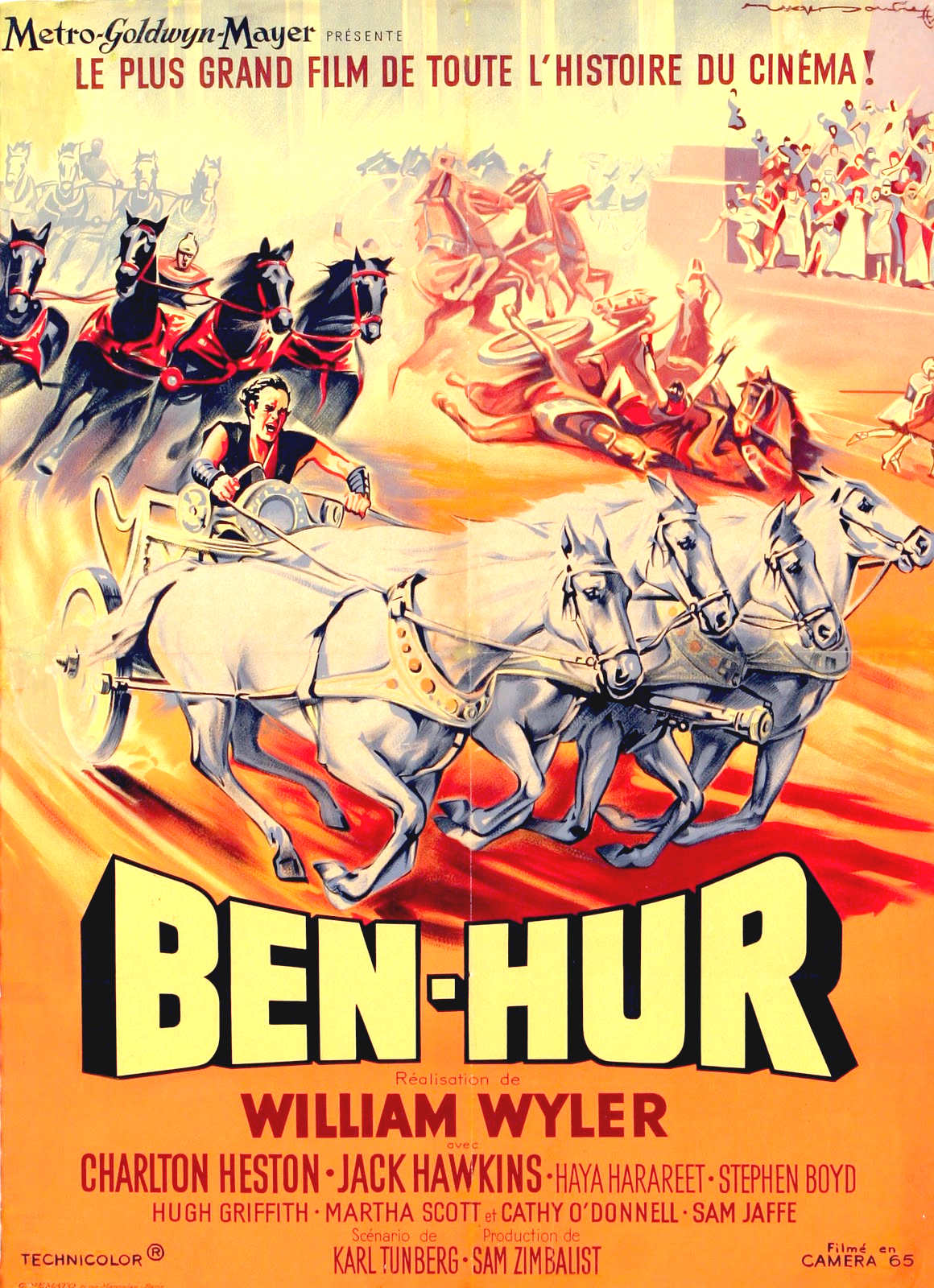

movie poster

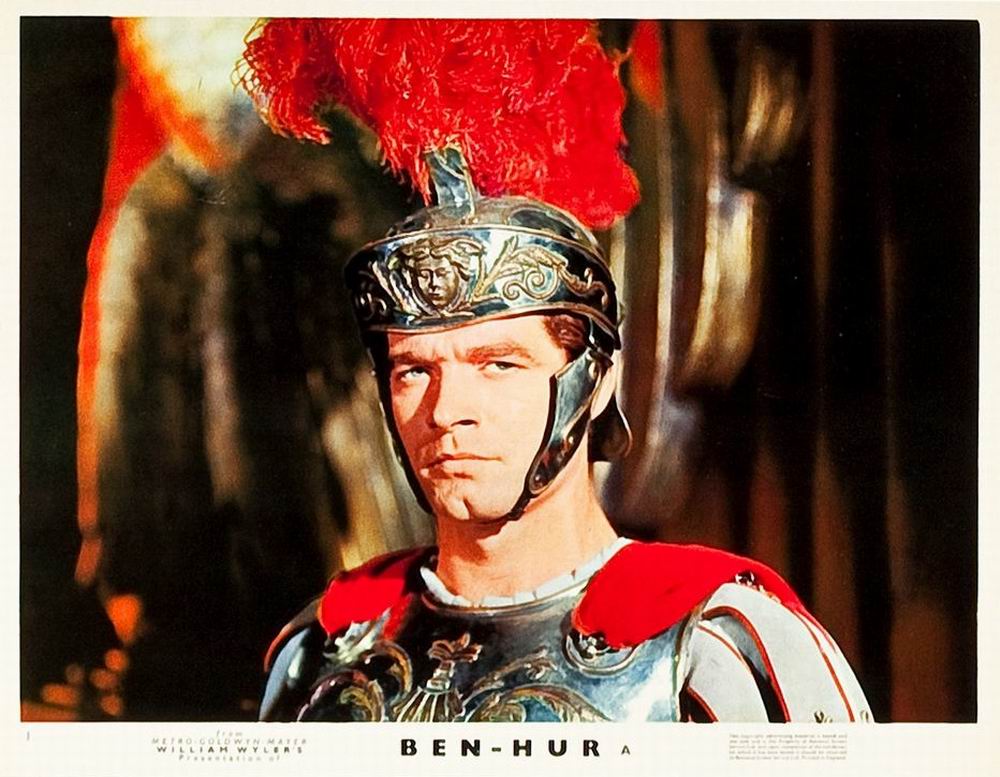

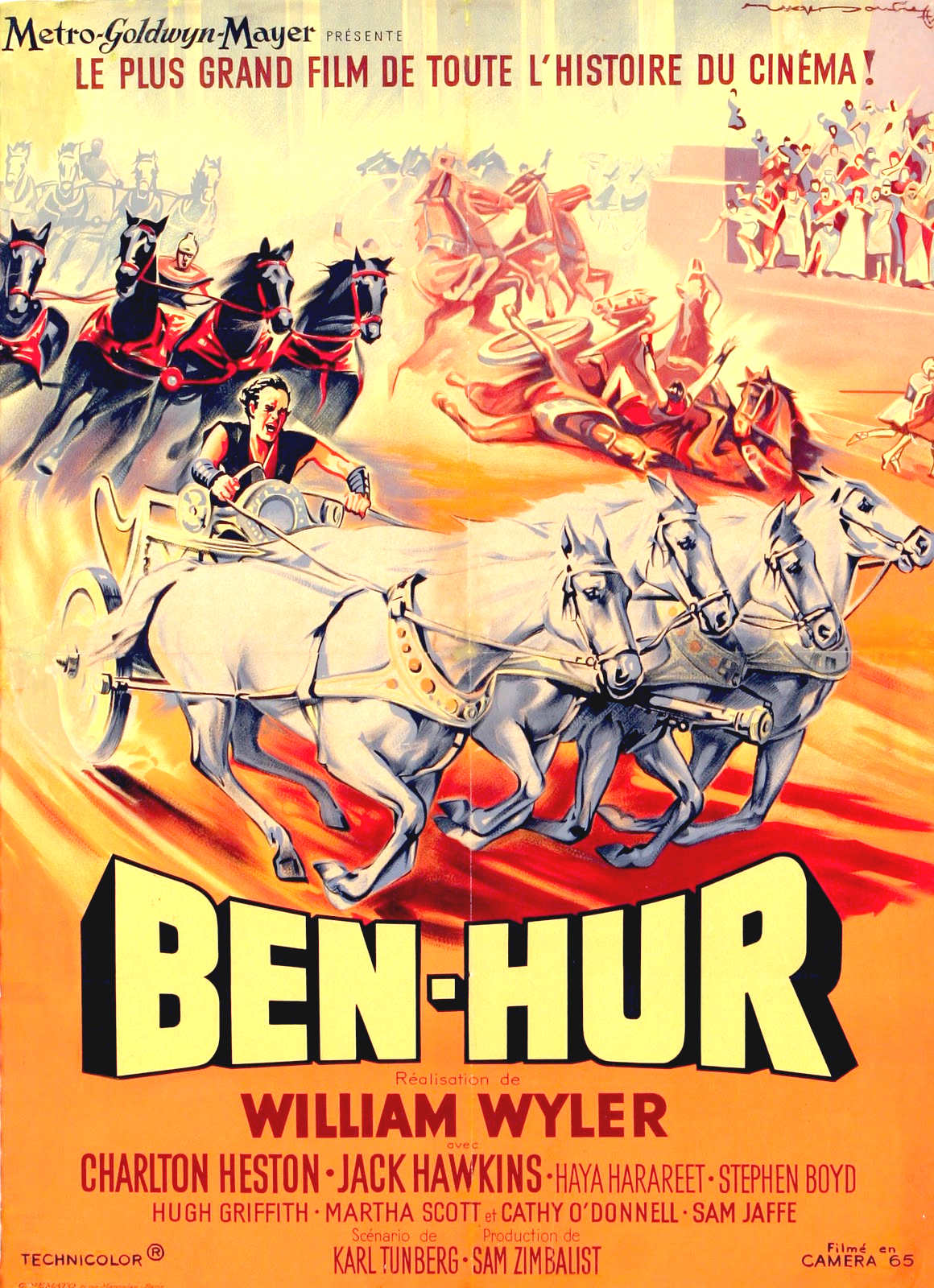

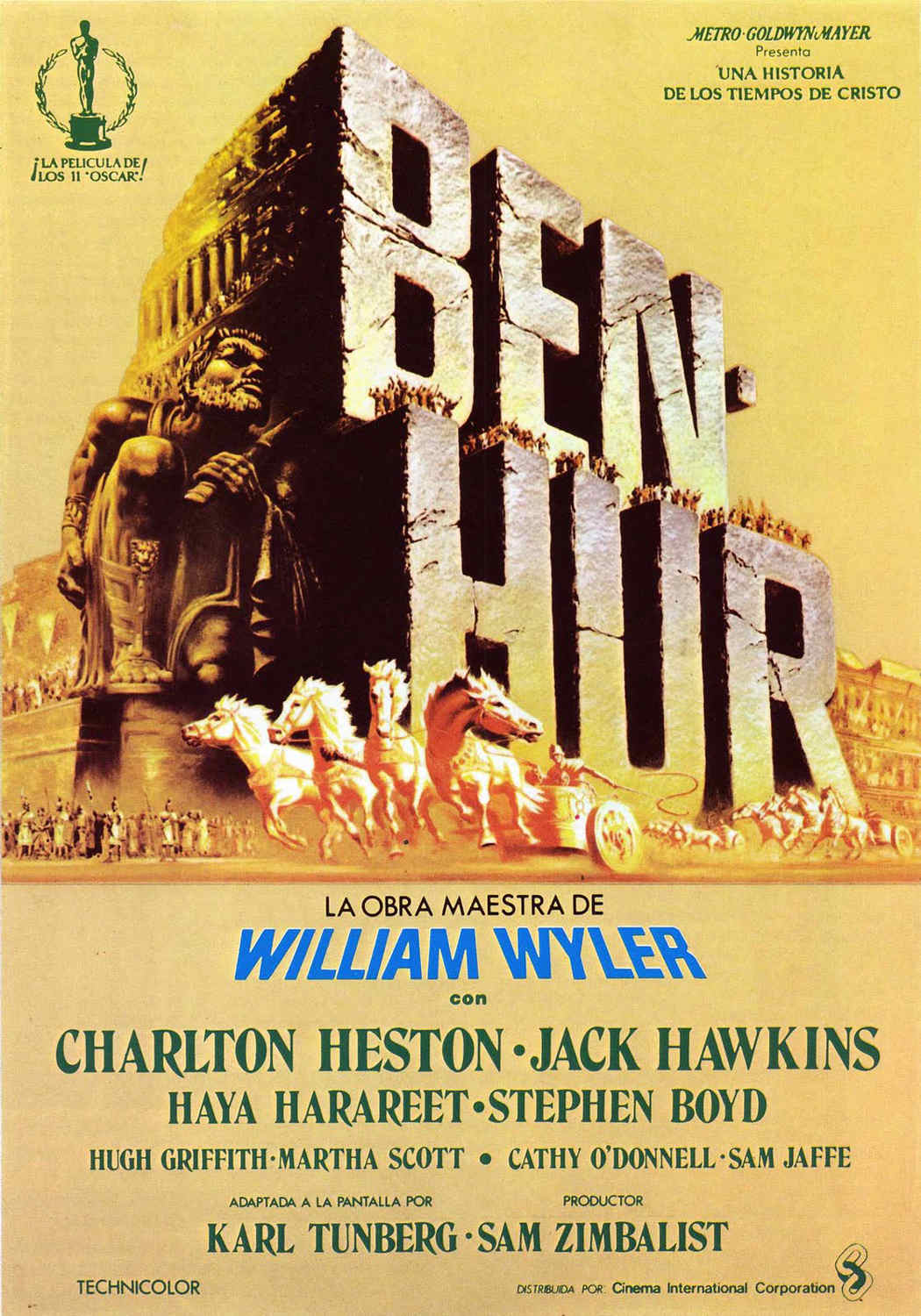

Ben-Hur is a 1959 American religious epic film directed by William Wyler, produced by Sam Zimbalist, and starring Charlton Heston as the title character. A remake of the 1925 silent film with a similar title, it was adapted from Lew Wallace's 1880 novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. The screenplay is credited to Karl Tunberg, but includes contributions from Maxwell Anderson, S. N. Behrman, Gore Vidal, and Christopher Fry.

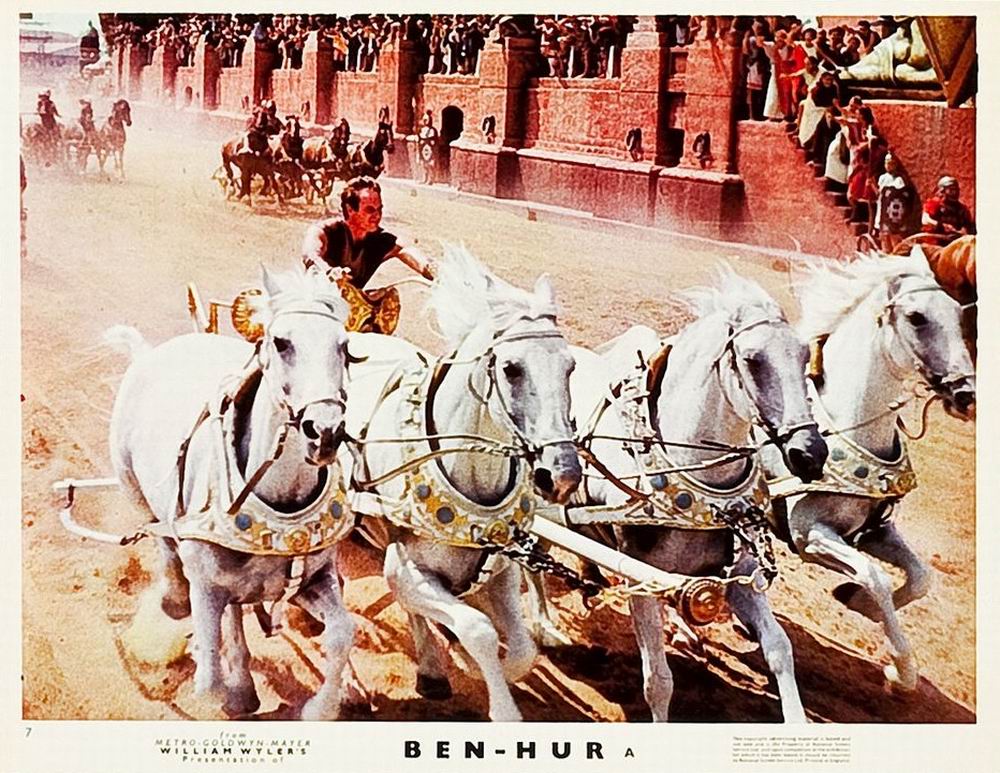

Ben-Hur had the largest budget ($15.175 million), as well as the largest sets built, of any film produced at the time. Costume designer Elizabeth Haffenden oversaw a staff of 100 wardrobe fabricators to make the costumes, and a workshop employing 200 artists and workmen provided the hundreds of friezes and statues needed in the film. Filming commenced on May 18, 1958, and wrapped on January 7, 1959, with shooting lasting for 12 to 14 hours a day and six days a week. Pre-production began in Italy at Cinecittŕ around October 1957, and post-production took six months. Under cinematographer Robert L. Surtees, executives at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer made the decision to produce the film in a widescreen format. Over 200 camels and 2,500 horses were used in the shooting of the film, with some 10,000 extras. The sea battle was filmed using miniatures in a huge tank on the back lot at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios in Culver City, California. The nine-minute chariot race has become one of cinema's most famous action sequences, and the score, composed and conducted by Miklós Rózsa, was at the time the longest ever composed for a film, and was highly influential on cinema for over 15 years.

Following a $14.7 million marketing effort, Ben-Hur premiered at Loew's State Theatre in New York City on November 18, 1959. It was the fastest-grossing, as well as the highest-grossing film of 1959, becoming the second highest-grossing film in history at the time, after Gone with the Wind. It won a record eleven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director (Wyler), Best Actor in a Leading Role (Heston), Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Griffith), and Best Cinematography – Color (Surtees); it also won Golden Globe Awards for Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Director, and Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture for Stephen Boyd. In 1998, the American Film Institute named it the 72nd best American film and the second best American epic film in the AFI's 10 Top 10. In 2004, the National Film Preservation Board selected Ben-Hur for preservation by the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

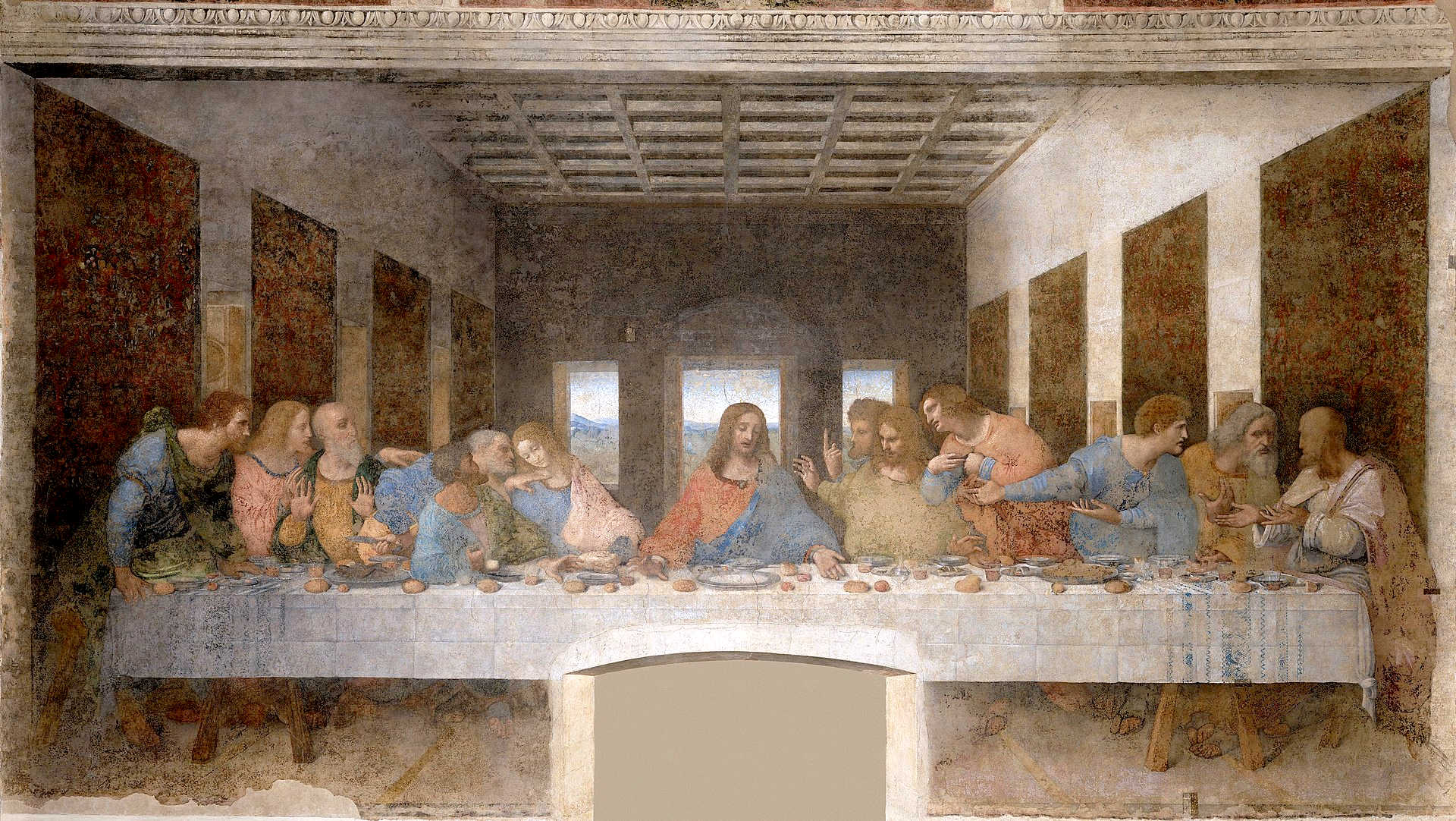

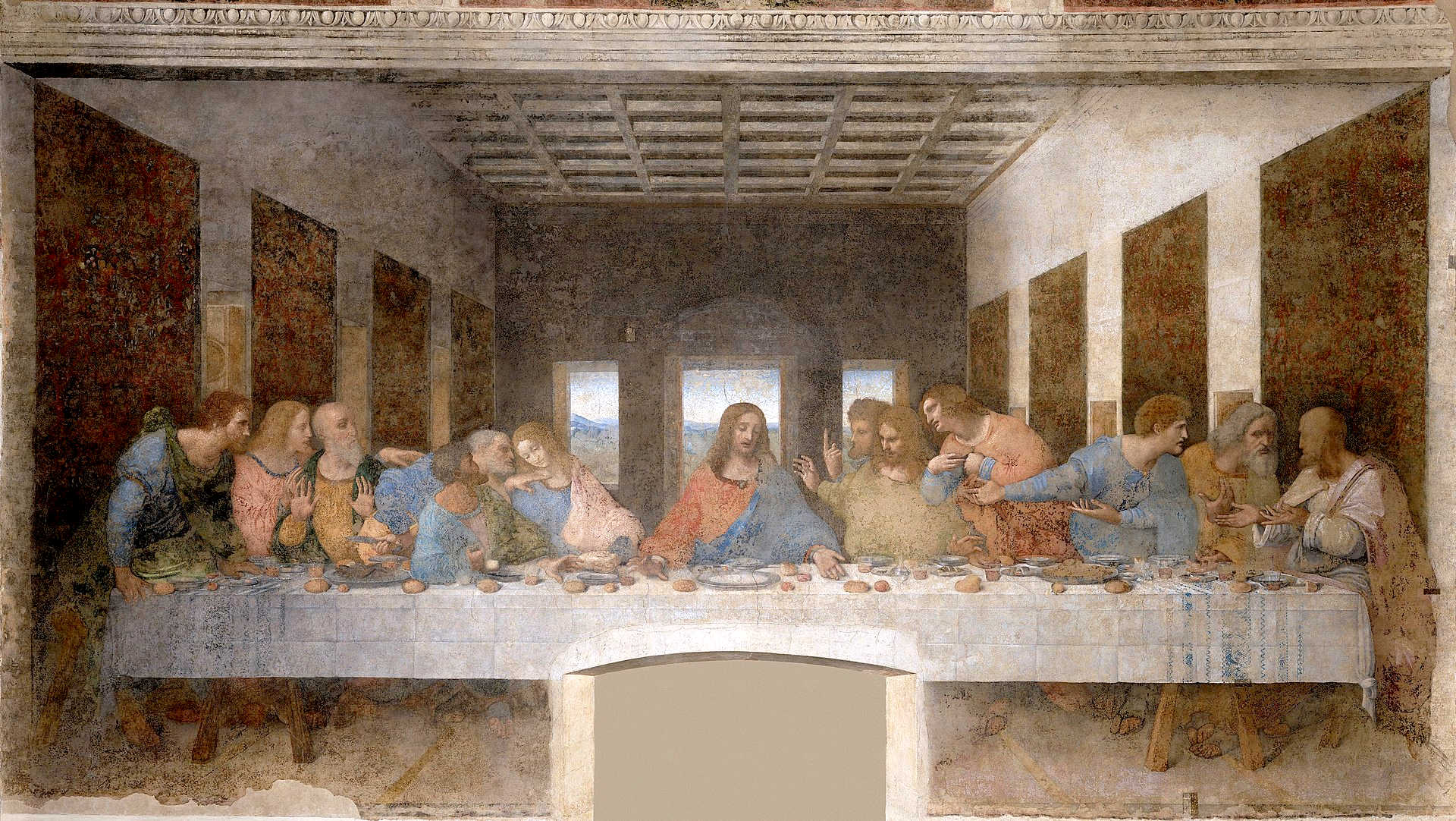

The

Last Supper, a painting by Leonardo da Vinci

PLOT

In the Prologue, a baby is born in Bethlehem among the shepherds and visited by Magi in a cave.

In A.D. 26, Judah Ben-Hur is a wealthy Jewish prince and merchant in Jerusalem, living with his mother, Miriam, and his sister, Tirzah. The family's loyal slave, the merchant Simonides, pays a visit with his daughter, Esther. Seeing each other for the first time since childhood, Judah and Esther fall in love, but she is betrothed to another. After several years away from Jerusalem, Judah's childhood friend Messala returns as commander of the Fortress Antonia. Messala believes in the glory of Rome and its imperial power, while Judah is devoted to his faith and the freedom of the Jewish people. This difference causes tension between the friends, and results in their split after Messala issues an ultimatum demanding that Judah deliver potential rebels to the Roman authorities.

During a parade for the new governor of Judea, Valerius Gratus, loose tiles fall from the roof of Judah's house. Gratus is thrown from his horse and nearly killed. Although Messala knows this was an accident, he condemns Judah to the galleys and imprisons Miriam and Tirzah. Simonides confronts Messala and is also imprisoned. Judah swears revenge upon Messala. As he and other slaves are marched to the galleys, they stop in Nazareth to water the Romans' horses. Judah begs for water, but the commander of the Roman detachment denies it to him. Judah collapses, but is revived when Jesus gives him water.

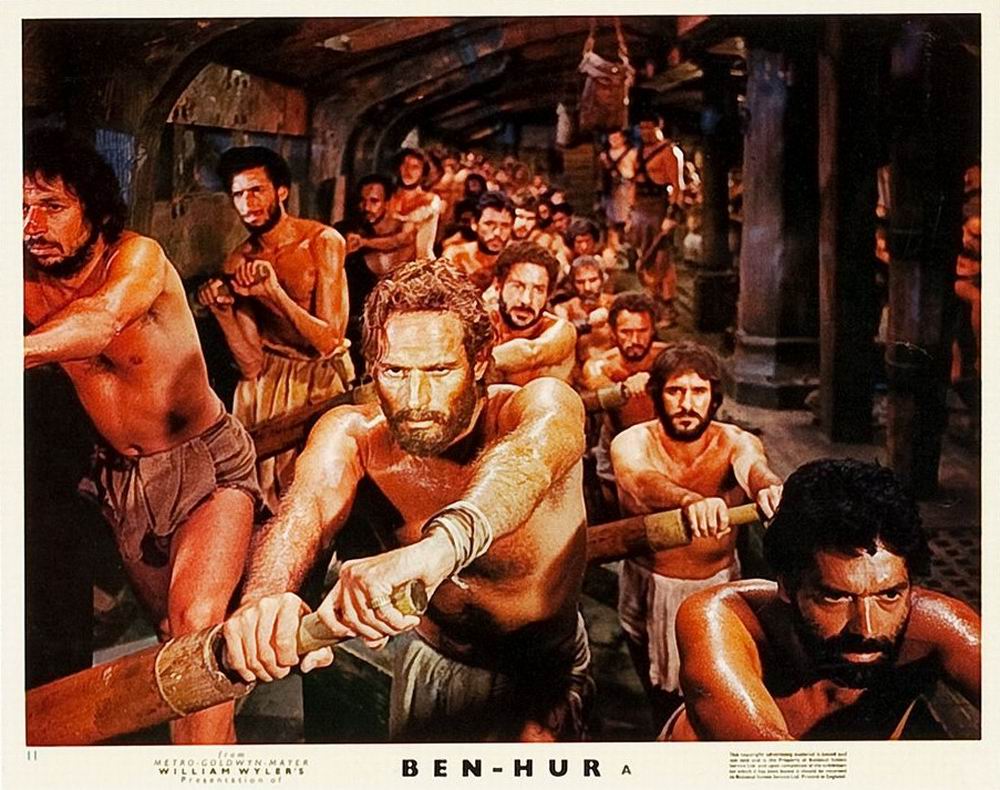

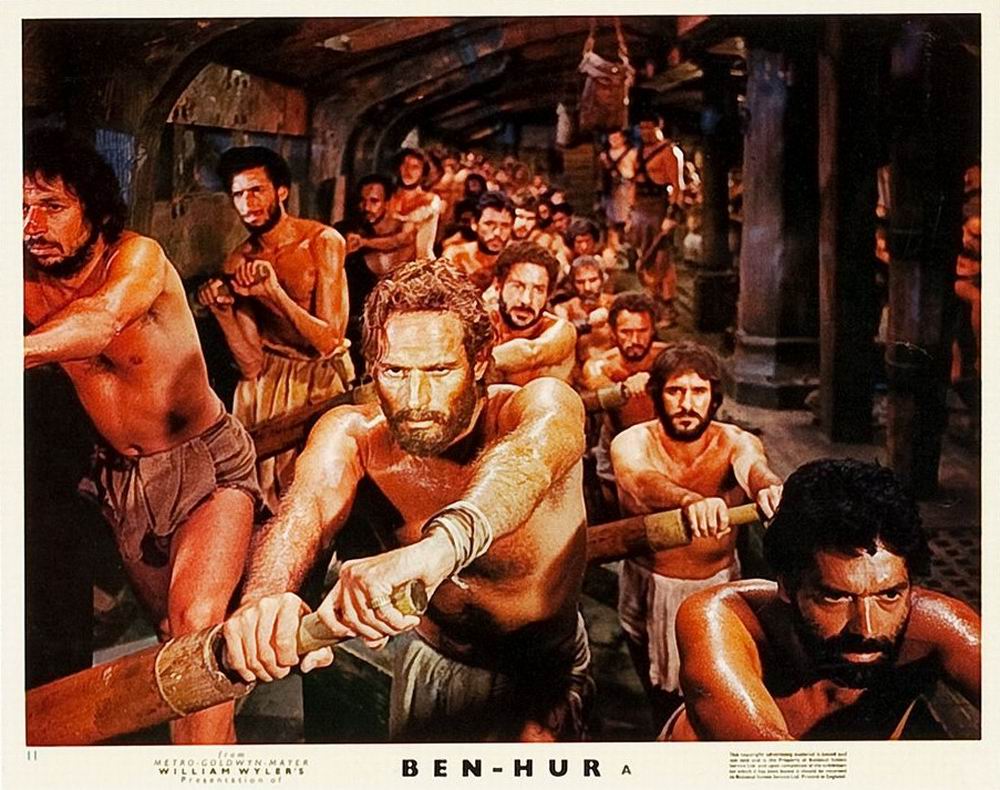

After three years as a galley slave, Judah is assigned to the flagship of the Roman Consul Quintus Arrius, who has been charged with destroying a fleet of Macedonian

pirates. Arrius admires Judah's determination and self-discipline, and offers to train him as a gladiator or charioteer. Judah declines. When the Roman fleet encounters the Macedonians, Arrius orders Judah to be unchained (thus if the ship goes down he has a chance of survival). During the battle, the galley is rammed and water flows in but Judah quickly overcomes the guard and frees the other rowers and makes his way to the battle on deck. Then he rescues Arrius who was thrown overboard. On a raft, Arrius believes he has lost the battle and attempts to fall on his sword, but Judah stops him. After they are rescued, Arrius is told his fleet had won a victory. Arrius petitions Emperor Tiberius to free Judah, and later adopts him as his son.

Judah becomes a champion charioteer, then returns to Judea. Along the way, he meets Balthasar and Arab Sheik Ilderim. After noting Judah's prowess as a charioteer, the sheik asks him to drive his quadriga in a race before the new governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate. Judah declines, even after learning that Messala will compete. Judah returns to Jerusalem. He finds Esther and learns she is not married and that she still loves him. Miriam and Tirzah contracted leprosy in prison and were expelled from the city. The women find Esther but beg her to conceal their condition from Judah, so Esther tells Judah they died. Judah smashes his family's mezuzah, then seeks revenge by competing against Messala in the chariot race. Sheik Ilderim goads Messala into making an enormous wager on himself.

During the race, Messala drives a chariot with blades on the hubs to disable his competitors. He attempts to destroy Judah's chariot, but wrecks his own instead. He is dragged behind his horses and trampled by another chariot, while Judah wins the race. Before dying, Messala tells Judah to search for his family in the Valley of the Lepers.

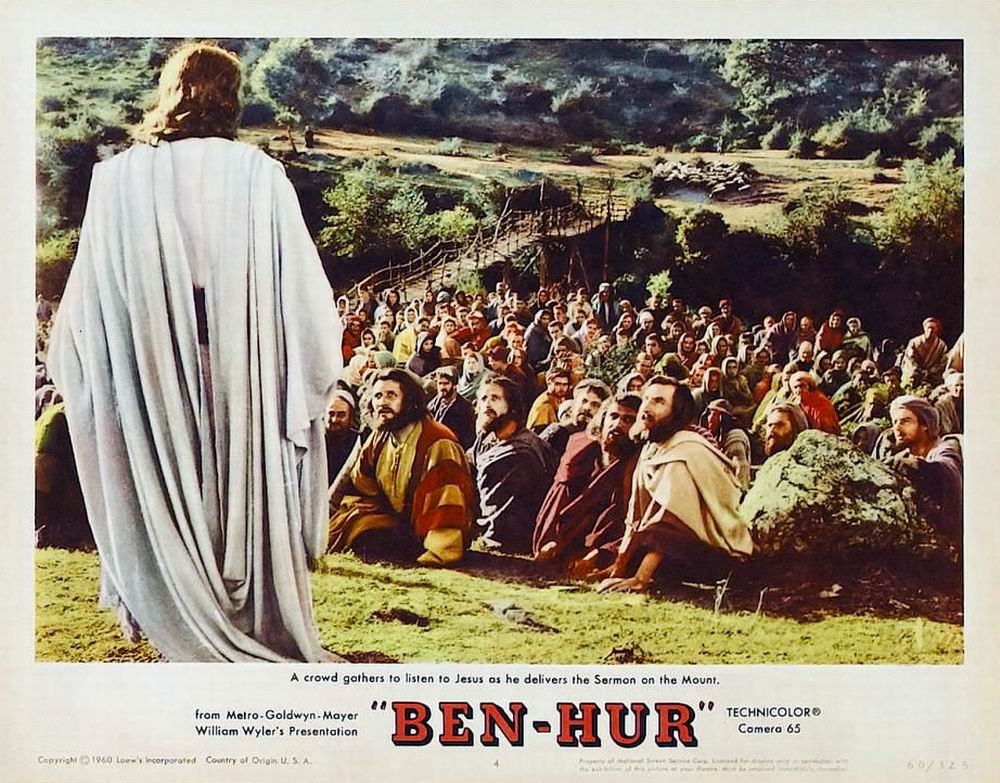

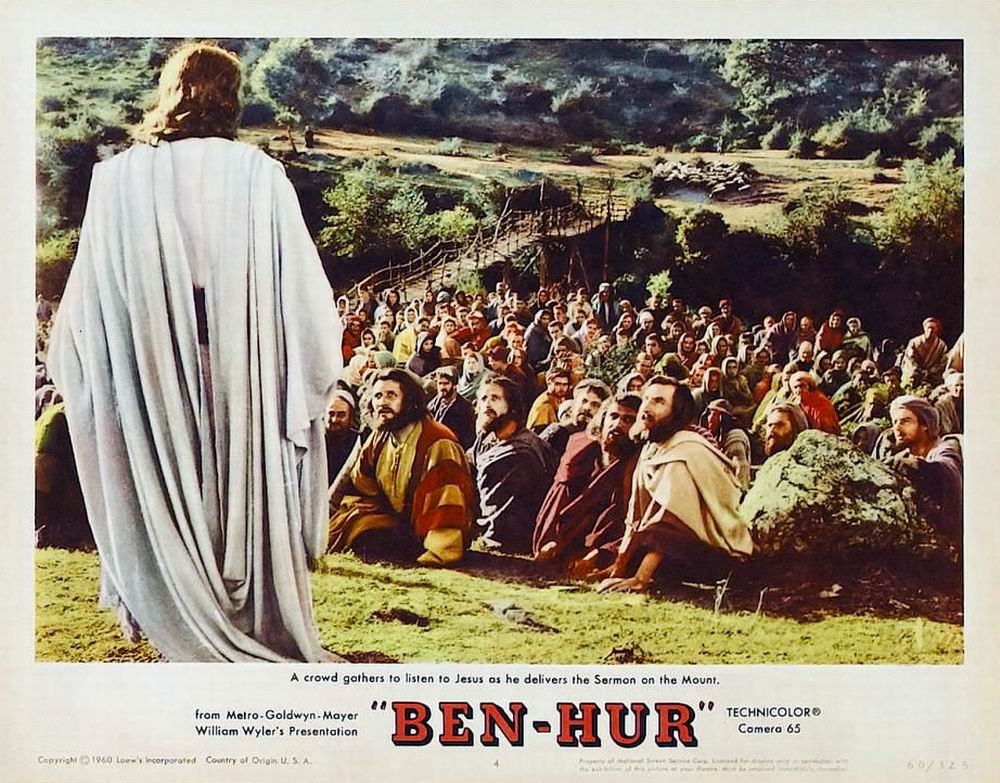

Judah visits the leper colony, where he confronts Esther while she delivers supplies to his mother and sister. Esther convinces Judah to not reveal himself to them. They stay with a crowd to hear what is possibly Jesus' sermon on the mount.

Judah visits Pilate and rejects his patrimony and Roman citizenship. He returns with Esther to the leper colony, reveals himself to Miriam and learns that Tirzah is dying. Judah and Esther take Miriam and her daughter to see

Jesus, but the trial of Jesus has begun. As Jesus is carrying his cross through the streets, he collapses. Judah recognizes him as the man who gave him water years before, and gives Jesus a drink. As Judah witnesses the crucifixion of Jesus, Miriam and Tirzah are miraculously healed.

Judah returns to his house, where he finds Esther, and his mother and sister now restored to health. The four embrace one another and rejoice at the miracle.

CAST

Charlton Heston as Judah Ben-Hur

Jack Hawkins as Quintus Arrius

Haya Harareet as Esther

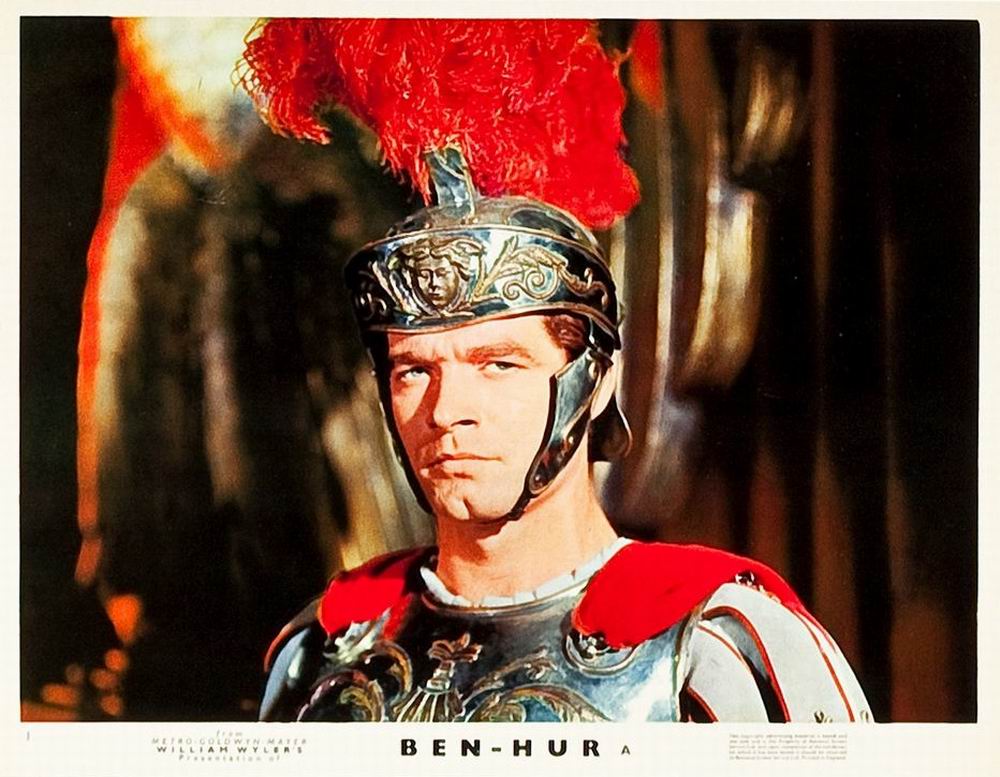

Stephen Boyd as Messala

Hugh Griffith as Sheik Ilderim

Martha Scott as Miriam

Cathy O'Donnell as Tirzah

Sam Jaffe as Simonides

Finlay Currie as Balthasar

Frank Thring as Pontius Pilate

Terence Longdon as Drusus

George Relph as Tiberius Caesar

André Morell as Sextus

Laurence Payne as Joseph

Claude Heater as Jesus Christ (uncredited)

José Greci as Mary, mother of Jesus (uncredited)

PRODUCTION & DEVELOPMENT

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) originally announced a remake of the 1925 silent film Ben-Hur in December 1952, ostensibly as a way to spend its Italian assets. Stewart Granger and Robert Taylor were reported to be in the running for the lead. Nine months later, MGM announced it would make the film in CinemaScope, with shooting beginning in 1954. In November 1953, MGM announced it had assigned producer Sam Zimbalist to the picture and hired screenwriter Karl Tunberg to write it. Sidney Franklin was scheduled to direct, with Marlon Brando intended for the lead. In September 1955, Zimbalist, who continued to claim that Tunberg's script was complete, announced that a $7 million, six- to seven- month production would begin in April 1956 in either Israel or Egypt in MGM's new 65mm widescreen process, MGM Camera 65. MGM, however, suspended production in early 1956, following Franklin's resignation.

By the late 1950s, the consent decree of 1948 forcing film studios to divest themselves of theater chains and the competitive pressure of television had caused significant financial distress at MGM. In a gamble to save the studio, and inspired by the success of Paramount Pictures' 1956 Biblical epic The Ten Commandments, studio head Joseph Vogel announced in 1957 that MGM would again move forward on a remake of Ben-Hur. Filming started in May 1958 and wrapped in January 1959, and post-production took six months. Although the budget for Ben-Hur was initially $7 million, it was reported to be $10 million by February 1958, reaching $15.175 million by the time shooting

began - making it the costliest film ever produced up to that time. When adjusted for inflation, the budget of Ben Hur was approximately $141 million in constant dollars.

One notable change in the film involved the opening titles. Concerned that a roaring Leo the Lion (the MGM mascot) would create the wrong mood for the sensitive and sacred nativity scene, Wyler received permission to replace the traditional logo with one in which Leo the Lion is quiet.

Lew Wallace's 1880 novel, Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, ran to about 550 pages. Zimbalist hired a number of screenwriters to cut the story down and turn the novel into a script. According to Gore Vidal, more than 12 versions of the script had been written by various writers by the spring of 1958. Vidal himself had been asked to write a version of the script in 1957, refused, and been placed on suspension for his decision. According to Vidal, Karl Tunberg was one of the last writers to work on the script. Other sources place Tunberg's initial involvement much earlier. Tunberg cut out everything in the book after the crucifixion of Jesus, omitted the sub-plot in which Ben-Hur fakes his death and raises a Jewish army to overthrow the Romans, and altered the manner in which the leperous women are healed. According to Wyler, Vidal, their biographers (see bibliography below) and the sources that follow them, Zimbalist was unhappy with Tunberg's script, considering it to be "pedestrian" and "unshootable".

The writing effort changed direction when director Sidney Franklin fell ill and was removed from the production. Zimbalist offered the project to William Wyler, who had been one of 30 assistant directors on the 1925 film, in early 1957. Wyler initially rejected it, considering the quality of the script to be "very primitive, elementary" and no better than hack work. Zimbalist showed Wyler some preliminary storyboards for the chariot race and informed him that MGM would be willing to spend up to $10 million, and as a result, Wyler began to express an interest in the picture.[30] MGM permitted Wyler to start casting, and in April 1957, mainstream media outlets reported that Wyler was giving screen tests to Italian leading men, such as Cesare Danova.

Wyler did not formally agree to direct the film until September 1957, and MGM did not announce his hiring until January 3, 1958. Even though he still lacked a leading man, Wyler took the assignment for many reasons: He was promised a base salary of $350,000 as well as 8 percent of the gross box office (or 3 percent of the net profits, whichever was greater), and he wanted to work in Rome again (in Hollywood on the Tiber, where he had filmed Roman Holiday). His base salary was, at the time, the largest ever paid to a director for a single film. Professional competitive reasons also played a role in his decision to direct, and Wyler later admitted that he wished to outdo Cecil B. DeMille, and make a "thinking man's" Biblical epic. In later years, William Wyler would joke that it took a Jew to make a good film about Christ.

RELEASE & BOX OFFICE RECEPTION

A massive $14.7 million marketing effort helped promote Ben-Hur. MGM established a special "Ben-Hur Research Department" which surveyed more than 2,000 high schools in 47 American cities to gauge teenage interest in the film. A high school study guide was also created and distributed. Sindlinger and Company was hired to conduct a nationwide survey to gauge the impact of the marketing campaign. In 1959 and 1960, more than $20 million in candy; children's tricycles in the shape of chariots; gowns; hair barrettes; items of jewelry; men's ties; bottles of perfume; "Ben-Her" and "Ben-His" towels; toy armor, helmets, and swords; umbrellas; and hardback and paperback versions of the novel (tied to the film with cover art) were sold.

Ben-Hur premiered at Loew's State Theatre in New York City on November 18, 1959. Present at the premiere were William Wyler, Charlton Heston, Stephen Boyd, Haya Harareet, Martha Scott, Ramon Novarro (who played Judah Ben-Hur in the 1925 silent film version), Spyros Skouras (president of the 20th Century Fox), Barney Balaban (president of Paramount Pictures), Jack L. Warner (president of Warner Bros.), Leonard Goldenson (president of the American Broadcasting Company), Moss Hart (playwright), Robert Kintner (an ABC Television executive), Sidney Kingsley (playwright), and Adolph Zukor (founder of Paramount Pictures).

During its initial release the film earned $33.6 million in North American theater rentals (the distributor's share of the box office), generating approximately $74.7 million in box office sales. It was number one at the monthly US box office for six months. Outside of North America, it earned $32.5 million in rentals (about $72.2 million at the box office) for a worldwide total of $66.1 million in rental earnings, roughly equivalent to $146.9 million in box office receipts. It was the fastest-grossing film as well as the highest-grossing film of 1959, in the process becoming the second-highest-grossing film of all-time (at that time) behind Gone with the Wind. Ben-Hur saved MGM from financial disaster, making a profit of $20,409,000 on its initial release, and another $10.1 million in profits when re-released in 1969. By 1989, Ben-Hur had earned $90 million in worldwide theatrical rentals.

Ben-Hur received overwhelmingly positive reviews upon its release. Bosley Crowther, writing for The New York Times, called Ben-Hur "a remarkably intelligent and engrossing human

drama". While praising the acting and William Wyler's "close-to" direction, he also had high praise for the chariot race: "There has seldom been anything in movies to compare with this picture's chariot race. It is a stunning complex of mighty setting, thrilling action by horses and men, panoramic observation and overwhelming use of dramatic sound." Jack Gaver, writing for United Press International, also had praise for the acting, calling it full of "genuine warmth and fervor and finely acted intimate scenes". Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times called it "magnificent, inspiring, awesome, enthralling, and all the other adjectives you have been reading about it". He also called the editing "generally expert" although at times abrupt. Ronald Holloway, writing for Variety, called Ben-Hur "a majestic achievement, representing a superb blending of the motion picture arts by master craftsmen", and concluded that "Gone With the Wind, Metro's own champion all-time top grosser, will eventually have to take a back seat". The chariot race "will probably be preserved in film archives as the finest example of the use of the motion picture camera to record an action sequence. The race, directed by Andrew Marton and Yakima Canutt, represents some 40 minutes of the most hair-raising excitement that film audiences have ever witnessed."

There was some criticism, however. Crowther felt the film was too long. Scheuer, while mostly praising the film, felt that its biggest fault was "overstatement", and that it hammered home at points long after they had been made. He singled out the galley rowing sequence, Jesus's journey to the place of crucifixion, and nearly all the sequences involving the lepers. He also lightly criticized Charlton Heston for being more physically than emotionally compelling. John McCarten of The New Yorker was more critical of Heston, writing that he "speaks English as if he'd learned it from records". Film critic Dwight Macdonald also was largely negative. He found the film so uninvolving and lengthy that he said, "I felt like a motorist trapped at a railroad crossing while a long freight train slowly trundles by." British film critic John Pym, writing for Time Out, was equally dismissive, calling the film a "four-hour Sunday school lesson". Many French and American film critics who subscribed to the auteur theory of filmmaking saw the film as confirmation of their belief that William Wyler was "merely a commercial craftsman" rather than a serious artist.

In December 1959, in her review for the London Sunday Times, the veteran English film critic Dilys Powell expressed many serious reservations about the film, but she still lavished praise on the film:

It is the best chariot race in the world, and no mistake. By now everybody has said so, and ... [my] only hope is that admiration may have special force when it is extorted from somebody who dislikes chariot races, shrinks from Biblical fiction and detests films ... which include the Crucifixion ...

... of the parts of this long, opulent film with its colour, its bright, sharp images, its stunning spectacle and its size ... I cannot complain. I still find that the whole is alien from me ...

... Nevertheless, if we must have films of this kind this is the one to have. After all, the spectacular scenes remain: the sea-fight, the Triumph, a magnificent storm and, of course, the chariot race—a scene superbly shot, superbly edited, superb in every way. I have never seen anything of its sort to touch it for excitement.

The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that 86% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 51 reviews collected, with an average rating of 8.30/10. The critics consensus reads, "Uneven, but in terms of epic scope and grand spectacle, Ben-Hur still ranks among Hollywood's finest examples of pure entertainment." On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 90 out of 100 based on 9 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".

The Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa cited this movie as one of his 100 favorite films.

AWARDS

Ben-Hur was nominated for 12 Academy Awards and won an unprecedented 11. As of 2023, only Titanic in 1998 and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King in 2004 have matched the film's wins. The only category that Ben-Hur did not win was for Best Adapted Screenplay (losing to Room at the Top), and most observers attributed this to the controversy over the writing credit. MGM and Panavision shared a special technical Oscar in March 1960 for developing the Camera 65 photographic process.

Ben-Hur also won three Golden Globe Awards – Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture for Stephen Boyd – and received a Special Achievement Award (which went to Andrew Marton for directing the chariot race sequence). Heston was nominated for a Golden Globe in the Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama category, but did not win. The picture also won the BAFTA Award for Best Film, the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Film, and the Directors Guild of America Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in a Motion Picture for William Wyler's masterful direction.

Ben-Hur also appears on several "best of" lists generated by the American Film Institute, an independent non-profit organization created by the National Endowment for the Arts in 1967. The "AFI 100 Years... series" were created by juries consisting of over 1,500 artists, scholars, critics, and historians, with movies selected based on the film's popularity over time, historical significance, and cultural impact. Ben-Hur appeared at #72 on the 100 Movies, #49 on the 100 Thrills, #21 on the Film Scores, #56 on the 100 Cheers and #2 on the AFI's 10 Top 10 Epic film lists. In 2004, the National Film Preservation Board selected Ben-Hur for preservation by the National Film Registry for being a "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" motion picture. It was listed as number 491 on Empire's 500 Greatest films of all time.

CHINESE BAN

The movie was banned in China under the regime of Mao Zedong for containing "propaganda of superstitious beliefs, namely

Christianity".

CLONING

& QUESTS FOR LIFE FILMS

A-Z

2001:

A Space Odyssey - Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C Clarke

Ben

Hur (Charlton Heston, Jack Hawkins) 1959

Fools

Gold (Matthew McConaughy, Kate Hudson) 2008

Indiana Jones and the

Last Crusade 1989

Jungle

Cruise, (Emily Blunt, Dwayne Johnson) 2021

Jurassic

World Dominion, (Chris Pratt) 2022

La

Amistad (Djimon Hounsou, Matthew McConaughey) 1997

Lara

Croft - Tomb Raider, Pandora's Box 2001

Lara

Croft - Tomb Raider, Cradle of Life 2003

Lara

Croft - Tomb Raider, Himiko 2018

Monty

Python and the Holy Grail 1975

Oblivion

(Tom Cruise, Andria Riseborough) 2013

Planet

of the Apes (Charlton Heston, Roddy McDowall) 1968

Sixth

Day (Arnold Schwarzenegger) 2000

The

Count of Monte Cristo (Jim Caviezel, Guy Pearce) 2002

The

da Vinci Code (Tom Hanks) 2006

The

Fly - (Jeff Goldblum, Geena Davis) 1986

The

Golden Compass (Nicole Kidman, Daniel Craig, Dakota Blue Richards)

2007

The

Greatest Story Ever Told (Charlton Heston) 1965

The

Medicine Man (Sean Connery, Lorraine Bracco) 1992

The

Pope's Exorcist (Russell Crowe, Julius Avery) 2023

The

Ten Commandments (Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner) 1956 Cecile B DeMille

Total

Recall - (Arnold Schwarzenegger, Rachel Ticotin, Sharon Stone) 1990

Uncharted

(Tom Holland, Mark Wahlberg) 2022

The

Cup of Christ is the Holy Grail, that has never been found, in all

searches through the ages.